This is a section of the newsletter The Curious Kat. Follow along as I write novel #4. If you join me here, you’ll be taking a deep dive in the psychology of drafting long form fiction. Who knows, the process may surprise you. What comes easily and what is hard? What kinds of choices am I making and why?

If you enjoy this post, please click onto the app and give me a “like.”

Last fall I took Robert McKee’s epic workshop on STORY: 30 hours of watching him talking on screen (very, VERY slowly) with no interruptions or interactions. He had a slight cough (a tic, to be honest) that almost made me lose my mind. How would I get through 30 hours? I regretted my substantial — and impulsive —investment.

Until, on day #4, I remembered the ability to play back the recordings at double speed.

McKee is a Hollywood icon who has given this same lecture hundreds if not thousands of times over the last few decades. I’m a little wary of him — he himself is not a successful screenwriter — while also being fascinated by his pithy directives.

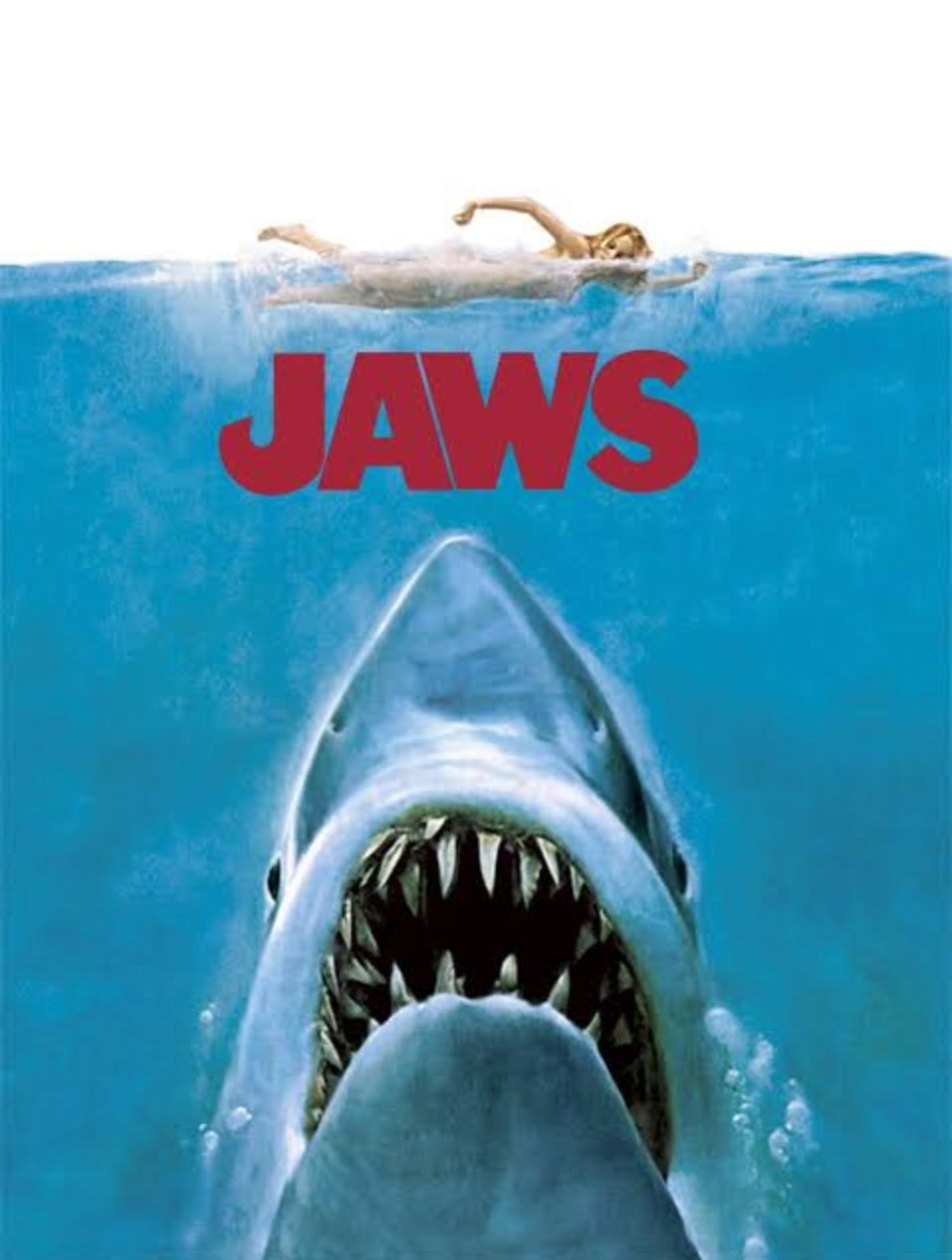

I like his certainty, his intellectual bent, and of course I’m attracted by the seductive and perhaps misleading idea that if you “follow the rules” you might just win the game. I’m also charmed that he mostly uses movies from the 1970s and 80s as reference points. It’s a fun trip down memory lane.

“Story isn’t a flight from reality but a vehicle that carries us on our search for reality, our best effort to make sense out of the anarchy of existence,” McKee writes. That sentence reflects the bombastic tendencies of his prose but also the essential soundness of certain of his observations. Art worthy of the name turns us not away from life but toward it.”

The New Yorker, Trapped in Robert McKee’s “Story,” March 9, 2023

Thirty-two fairly pithy directives

I’ve just gone through my notes, so here are the 32 pithy pronouncements about story, pulled from McKee’s lectures. (Note that, generally, you can substitute “reader” for “viewer” and vice versa, though the rules of novel writing and screenwriting are of course quite different.)

Q: What do audiences/ readers want? A: They want to feel: curiosity (how will it turn out?); surprise (they gain insights); and concern (they’re looking for the center of good).

Facts are what happens, truth is causality, ie. WHY it happens, and story is how life changes as a consequence.

Change only becomes meaningful (and interesting) when it’s expressed through conflict.

In long form story telling, acts build to a series of turning points that lead to massive change, both inward and outward.

Be true to your world and characters, but unique in your choices.

We see a person’s true character in the choices they make under pressure.

People have multiple selves: public (outward facing), personal (interacting with others), private (what they dream of, internal arguments they don’t share) and hidden (subconscious). Explore them all.

The inciting incident, which begins the change in the story, is when the reader asks, “how will this turn out??” and it must happen on stage and be a fully executed event.

Your protagonist should have a conscious pursuit (which changes again and again) as well as a contradictory subconscious desire (which does NOT change).

The protagonist should be the one to settle the conflict in the story. ie. s/he cannot be passive.

If readers don’t “like” your protagonist, that’s okay as long as they have some empathy for them ie. there’s something within the character they identify with.

Don’t ask yourself, “what would this character do?” Ask, “what would I do if I were this character?”

People take actions (make decisions) based on what they think is the easiest path to getting what they want. Story is what happens in the gap between their expectation of what will happen and the reality of what happens.

In every scene, there should be gaps between expectation and reality.

Story is most exciting when a character’s tactic (trying to get what they want) gets them an unexpected result and they must therefore act out of necessity — it’s risky, and they may lose something important.

What is crisis? It’s when there’s only one last action we can take beyond which lies success of failure.

In the middle, stories must have complications on multiple levels — physical, social, personal and inner — to keep them going.

McKee used an early scene from he 1979 film Kramer vs Kramer to explain point #18 below: we’re surprised that Kramer doesn’t know how to make breakfast for his son => this gives us deeper understanding of his character => we understand why his wife left him => viewers are satisfied about this insight. Turning points need good set ups; they create surprise => curiosity => insight => pleasure for the reader.

Introducing complications: characters can be faced with four forces of antagonism that stack up against their own abilities: 1) unconscious mind 2) personal relationships 3) society 4) institutions and reality (ie. time, space, objects).

Choices matter when risk is involved.

François Truffaut said that climax is the combination of spectacle and truth. McKee adds that a moving climax can be understated (as in the movie, The Reader) but must address the core conflict and value system examined in the story.

In character driven stories, characters’ choices under pressure change the course of their lives: the focus is on the characters’ actions/choices (the narrative is shaped through their personality and desire).

In plot driven stories, events happen that are outside the characters’ control and they must react to them.

Storylines are thought of as melodramatic when readers/ viewers don’t believe the emotion or subtext in a scene.

Mystery = behind which door is the monster? (this is about facts)

Suspense = you open the door and see the shadow of an ax: how will it turn out?? (this is about fear and concern)

Dramatic Irony = you head to closed door and viewer/ reader knows there’s a monster behind it: we’re interested in the HOW and the WHY (we’re concerned)

Give the reader only what they need to know in that very moment.

People turn pages because of their curiosity and concern.

Characters with contradictory personalities elicit curiosity. Writers must dramatize those contradictions.

Dialogue is not conversation, it’s action. The purpose of every line of dialogue is to cause an intended reaction.

Repetition of imagery creates meaning through a subliminal image system the audience/ reader picks up on. It shouldn’t be too obvious.

If you use coincidence in your work, acknowledge it as a coincidence and it will be accepted.

Survival depends on change and adaptation, and yet your identity — your values, who you really are — must not change. This is the core conflict of our lives.

Sounds like it was worth it in the end:)! Great notes, thank you.

This is so great! Thank you for taking the time to write these points up and share them! I did his course years ago and really appreciate the reminders. We KNOW so much of this, but it still feels fresh reviewing it.