This is a section of the newsletter The Curious Kat. Follow along as I write novel #4. Opting out of these updates (and sticking with the newsletter) is easy: go to the footer of this post, select "Unsubscribe" (next to “Anatomy of a Novel”) and click "Turn off emails."

If you join me here, you’ll be taking a weekly deep dive in the psychology of drafting long form fiction. Who knows, the process may surprise you. What comes easily and what is hard? What kinds of choices am I making and why?

If you enjoy the post, please comment in the app and/or send me a quick heart!

Wrestling with the notion of ‘emotional availability’

Last week I finished Miranda July’s novel, All Fours, and while I initially didn’t really “get” it - and I almost quit reading, about half way through I started enjoying it. What was the turning point when I became committed, and why? This always intrigues me because of what it might mean in terms of my own work.

If you’ve read All Fours you know that close to the beginning the main character (a semi-famous unnamed artist in her mid-forties) spends $20,000 hiring a decorator to re-do a motel room where she’s landed by accident. She’s checked out of her life and into the motel, and becomes sexually obsessed with a young dancer. Money isn’t an object; we get that she doesn’t make decisions the same way “normal” people do (hence investing in glamming up a motel room).

What I’m trying to figure out here is this: as readers, how much leeway will we give characters we don’t yet fully understand? Is there a moment when we say, I don’t buy this, and we simply stop enjoying the book?

I think that’s what happened when I was reading All Fours. The decision to pour money into the sleazy motel room was interesting… but not really believable, at least to me. I just didn’t buy it, and so it threw up questions about the veracity of the character. I started feeling confused about her motives and personality and that created emotional distance.

I love it when characters make unexpected choices. But at what point do we lose the reader if/ when our characters make odd decisions or start breaking rules?

In the past when rejecting my work, editors have said things like, “I’m afraid I never quite built the emotional investment in her relationship that I would need,” and “I gradually began to lose affection and then interest in XXX,” and “I felt a bit too much emotional distance from the characters.”

It’s a recurring theme: readers need to feel emotionally invested in the characters to keep turning pages, and yet why and how this happens is quite the mystery.

What makes a reader BEGIN to feel - and CONTINUE to feel - emotionally connected to a protagonist?! Does the character have to show vulnerability? Some ethical inclination we admire? Does s/he have to love - or save - a cat??*

For God’s sake, if you have an answer or a theory, please let me know:

*I’m referring to the how-to book “Save the Cat” which posits that if we have a character do one noble thing early on in our story, readers will forgive them anything.

The devil is in the details

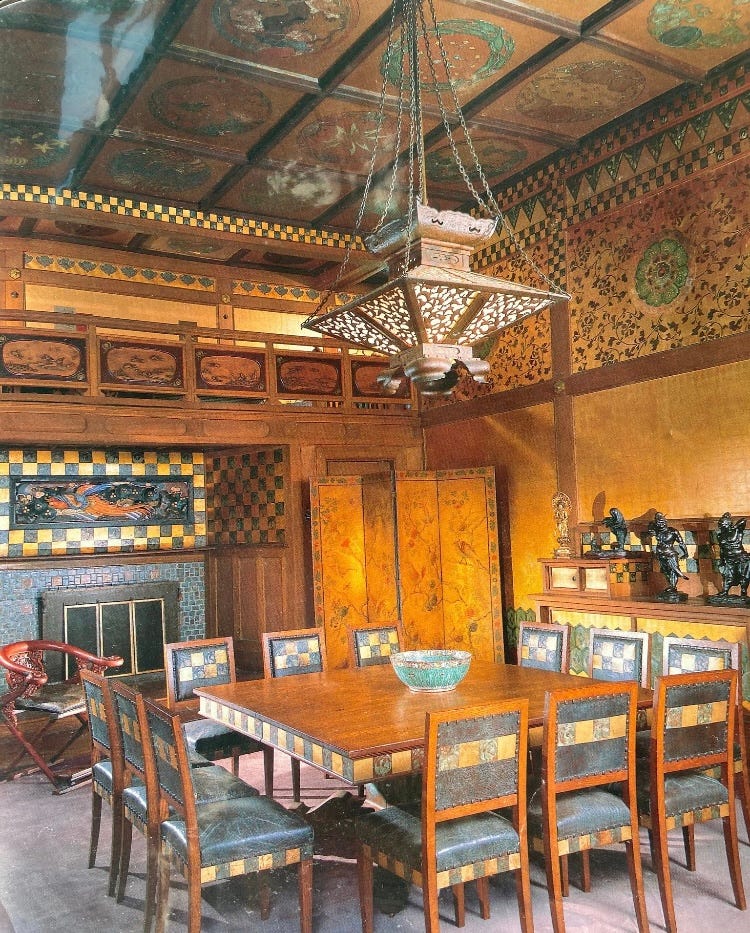

In Part II of my novel, 15-year old Beatrice Pfennig is forced to work at Sho Fu Den where she’s thrown into a world so unfamiliar and rife with hidden tensions (jealousy, hubris, racism, classism) that the experience blows her life apart.

I want this part of the book to be weird and exciting and overwhelming, and absolutely transformative. Beatrice is given incredible opportunities AND she’s betrayed and underestimated. She falls wildly, madly in love AND she learns she can trust no one. She learns more about the world and human nature in four years than her parents (German immigrants) learned in four decades.

Knowing this section has to move along the narrative while being realistic, quirky (maybe), and fresh (above all), is a tall order. How do I avoid cliché?

There are a few key questions haunting me about this part of the story:

As a new maid, how does Beatrice have access to the inner circle?

How does she subvert expectations? Meaning, literally, what are the actual things she does that make her stand out from all the other girls and women who’ve worked at SFD before? How does her exceptional intellectual capability reveal itself to others - especially to the Takamine family?

Who is her enemy, here? Do the other maids support her? How does she get on with the Japanese maids and workers?

What’s her relationship with Takamine’s wife, Caroline, the mother of the twins?

Does Bea have a secret confidant - someone who supports her?

How many twists and turns do I want/ need Beatrice to take in this section? What does she get wrong and what does she get right?

Since I have to start somewhere, I want to answer the first question first: without access to the inner workings of the entire house (not just the kitchen), Bea wouldn’t see and experience enough to rock her world. How does a maid who is busy and low on the totem pole in terms of power have time and freedom to roam and observe?

Charles Baxter to the rescue

While doing yoga, a memory popped into my head - some great advice I got from Charles Baxter at a Muse & the Marketplace writing conference almost ten years ago.

“Do you have a Request Moment? A character cannot be passive if s/he has been given a request and asked to do it within a certain amount of time. This puts a dramatic moment out into the world. It creates an intriguing understanding of what certain people owe each other. Many of us live under the shadow of requests that have been made to us… this is inherently dramatic. Requests set a chain of cause and effect into motion. (Remember the opening of the Godfather in which Don Corleone is asked to avenge a young girl's rape?)”*

Perhaps Caroline Hitch, the American wife of Takamine asks Beatrice - who can’t refuse, of course - to spy on her husband and children and report back to her. Bea becomes indebted to her mistress, keeping secrets for and with her - while wrestling with her conscience, and uncovering various sordid/ fabulous secrets.

In a way, Caroline is a renegade just like Bea, but they are also opposites. Caroline can’t live up to the expectations of the Japanese, nor does her marriage resemble the kind of life she thought she was choosing when she made the radical decision to marry Jokichi.

Bea manages to find strength in the hand she’s been dealt, whereas Caroline remains part of the system - trapped by her adventurous nature and by her gilded cage (cliché alert!). Bea, in contrast, transforms herself utterly.

This might make a nice contrast. I’ll have to stew on it.

In reality, I expect that Caroline was neither cowed nor insecure, but what do I know? And do I need to stick to reality, anyway??

Here she is. What story does her face tell? Her posture?

*I’ll link to the tips I got from Baxter in my next post.

Next week: updates on my sexy reading forays and a big new idea!

I feel characters just like real people are mirrors to us and most time of our hiden self. I think that the difference between a bad guy and a good one depends on the type of reflection he/she radiates on us. At the end i am capable to perceive the roles each plays in the comedy or tragedy that i am watching and my impression is that the bad guy is not that bad neither the good is that good. Are just roles, more difficult is to play the bad one...

I love this new section of your newsletter! It strikes me as so generous that you are taking the time to share the details of your process, especially the questions you are wrestling with and how you are noticing what you need to do to take care of your creative energy. I am learning something with each post, and you are making it all sound so pleasant, even though I know it is damn hard work with plenty of frustrating puzzles to solve.

That portrait of Caroline makes me want to reach back in time and raise her up off her knees, unravel that sash, toss the heavy-looking kimono out the window and take her for a run through wet grass.

I don't have any words of writing wisdom regarding some of the issues you presented in the post, but I am thinking of some questions posed in a recent workshop on Exploring Conflict and Change Through Poetry, facilitated by the Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama. I have been thinking about these particular questions in my own writing of the moment. "What are the griefs of the characters? What is your measuring of the griefs? How are the characters punishing each other? What kinds of power does each character hold? How do they measure each other's power? What is the level of choice being experienced by the characters? i.e. Can they leave? What would happen then?" Just a share for you, since you've shared so much with this reader! Looking forward to the next installment!

(Questions adapted from Change & Conflict - Motivation, Resistance and Commitment. Chapter by Eric C. Marcus in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice.