This is a bi-weekly section of the newsletter The Curious Kat. Follow along as I write novel #4. If you join me here, you’ll be taking a deep dive in the psychology of drafting long form fiction. Who knows, the process may surprise you. What comes easily and what is hard? What kinds of choices am I making and why?

If you enjoy the post, please click on the heart or comment in the app!

A few summers ago, while I was waiting on my former agent to give me her thoughts on the draft of my new novel, Madame B. (this was about six months after I’d submitted it to her and after about ten promises to read it by a certain date), I decided to write a screenplay.

I bought a book called How to Write a Screenplay. I watched a few movies closely. I spent about a month writing a script for a film. It was incredibly fun.

It’s pretty obvious to any Hollywood (or TV-land) outsider that writing a script and getting it made is at least as difficult as getting a book published. Yes, people actually still watch movies and TV shows, but there are also ten billion wanna-be screenwriters out there and making movies and shows is costly.

(This film with Olivia Coleman, The Lost Daughter, reminds me a bit — in tone and theme — of my Ibiza novel, Madame B. I highly recommend it.)

BUT…

… for me, as a novelist writing a screenplay, it was SO FREEING. It exercises completely different muscles. And it’s a low stakes maneuver since I have few expectations of “success.”

Sometimes when you severely limit your story options as a writer, you’re forced to be more creative.

This is grossly simplified, but it requires thinking mainly about 1) actions that people take 2) dialogue and 3) clues in someone’s appearance or in the setting that resonate with the storyline and theme.

And it’s short — there are strict rules about how long a screenplay should be and you really don’t gain anything by breaking those rules.

Sometimes when you severely limit your story options as a writer, you’re forced to be more creative. You’re not worrying about which words (or metaphors) to use to describe some elusive feeling or shift in mood or desire, you are SHOWING it with one quick shot — or one lingering moment. And then you move on.

Since novelists like me know so little about the process of getting a movie made, we can write away happily while that bully within is smoking a smelly cigar and can’t shower us with belittling invectives — that bully just has no damn idea what we’re up to.

Adaptations take a long time (and a lot of $$$) to come to fruition

My first novel, The Forgotten Hours, was optioned a couple of years ago by an independent producer from SheSpun Productions. She paired up with a young screenwriter and they wrote a pilot, sketched out an entire series and came up with ideas for three seasons of television and a spin off.

They made a lot of changes to the story. They added new characters and shifted scenes around, but they kept the essence of the novel: that tricky, complex relationship between a doting daughter and a loving yet unpredictable father. How we wrestle with “truth,” and the fact that everyone’s perception of reality is different. How summer communities and summer love and summer friendships impact us in ways that reverberate throughout our adult lives.

It’s fascinating to see the bones still there in this new visual format, while so much of the surrounding storyline has been tweaked, cut or radically altered.

They’re now working on funding, and that basically starts with securing talent. Some actors can greenlight productions just by showing interest (see this fascinating New York Times article “Sex, Death and Nicole Kidman”). I’m so grateful to be part of the process; it’s pretty extraordinary to watch other people invest their time, energy and creativity into bringing to life an idea that was hatched in my own brain when I typed a bunch of words into a computer, wondering if they would ever add up to something meaningful.

“No bully from within shall prevail” over you

The bully inside us maintains a laser sharp focus on our weaknesses. The trick is to find ways to shut off the bully’s stream of insinuating commentary. As I discovered a few years ago, one way to do that is to try something new and have zero expectations about outcome.

It’s been a difficult few months for my new project, and I’m surprised to be in a place where I’m excited about finding new ways into my Sho Fu Den story.

A few weeks ago I was at a gathering amongst author friends to share new writing. I’m not one to share works in progress — there’s just so much finessing that goes on between drafts that getting feedback on early versions is often not very helpful for me, and can, in fact, be harmful.

Workshops in which individual pieces are critiqued must be ‘safe spaces’ in order to be useful to the person being critiqued. What this means in practice is that I — or whoever is the instructor — guides and then redirects the conversation with the goal of giving the writer exactly what s/he needs at that moment. When I’m teaching, it’s my job to ensure that we’re meeting writers right where they are.

I’m not suggesting it’s good to go soft when critiquing (there’s always room for improvement). What I’m saying is this: being rigorous, specific, and kind is the way to have the most positive impact on someone’s work. You can only do that when you’re on the writer’s side, giving them what they need to hear with some empathy.

But in writing groups no one’s in charge and things can go off the rails. Our meeting went awry and we’re going to try it differently next time. It spurred me to switch things up on my end, too. Since my main goals this year are to be bold and to find more joy, I’m going to shift my focus from prose to writing for the screen and TV, at least for the time being.

Being rigorous, specific, and kind is the way to have the most positive impact on someone’s work

I listened to “Story” giant Robert McKee’s lectures and am going to comb through them again for the wisdom and insights I can use for future novels. And for the next ten weeks I’m taking an online, advanced screenwriting class through GrubStreet, taught by Mark Fogarty.

After my first class, I’ve written a pitch for the limited series, and a log line for the pilot.

It’s terrible! Who cares!

I’m excited, so I’ll take it as a win.

Bits & bobs

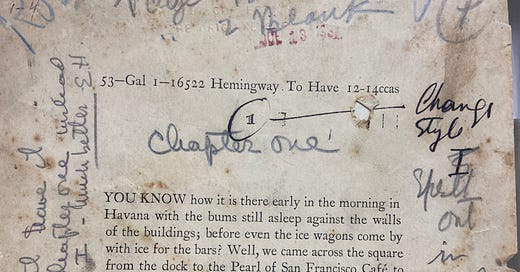

Do those Hemingway copy edits in the top picture say “Bastard” — anyone know if that’s a technical editing term, lol?

Stay posted for a new online class I’m going to be teaching, CRAFT INTENSIVE, launching in March. I’ll announce it in the next newsletter.

Meanwhile, here’s a novel writing class, The Novel Blueprint Workshop — taught by Lynne Griffin — that also starts in March; might be a good fit for some of you.

I just finished Intermezzo by Sally Rooney. It blew my mind. More on that soon.

Your hunch is right; "bastard" is a technical term. In traditional bookmaking, after the title page and its verso (or back side, usually the copyright page), comes the half title or bastard title page--title only--which is silently considered page 1. Its verso, which is blank, is silently page 2. The text begins on the next righthand page, which is the first to get an expressed folio, or page number. All that "front matter" can get pretty complicated in some books!

Thanks for another great post!

Amen to that! There are plenty of real bullies out there; we don't need one inside our heads! I'm interested you are moving to screenwriting for now...